step by step 一歩一歩

We made tofu together.

At the back of the old Chiang Mai market.

During the pre-dawn dark.

For a month.

From Monday to Friday starting at 5am.

The ritual took three hours.

No more, no less.

On the minute.

Like a shinkansen (bullet train) leaving Tokyo station.

It was a science and an art, and at the end, a spiritual awakening.

It was majestic.

The only time he spoke to me during those thirty peaceful days was in the first fifteen minutes of the first day and the last fifteen minutes of the final day.

He explained how a Japanese man came to make bean curd in Northern Thailand.

“I was born in Kyoto and crossed into Northern Thailand via the Burmese border at the end of the Second World War. We were Imperial Army foot soldiers fleeing the Allied troops.”

I tried to interject but he cut me short with a smile.

“That story is for another day.”

He looked up at me and his eyes softened in memory of obvious pain and loss. I did the mental sums. It meant he was well over ninety years of age. He did not look a day over seventy. A very healthy, fit and happy seventy!

“My mother made bean curd at a famous Kyoto tofu shop called Sayadoufu Moriku. It must be well over 140 years old by now. People travelled up the Katsura River to sample the beautiful, silken tofu she and the other women made for their master.

As a schoolboy I would accompany her to work and watch her start the day.

My mother made sure her working station was ready before she commenced.

Everything had to be just so.

She would begin and I would watch.

Day by day.

I would then walk to school.

Life was simple for a boy in Kyoto.

Summers were hot and still, and it snowed during winter.

The Kyoto temple bells would chime and cavort in the heavy air and then bounce into the ring of luxurious forest and echo back over the ancient, volcano crater.

The bells had a life of their own as the noisy melody clattered down the stone paved lanes and through the tatami screens.

Meat was scarce so tofu provided the protein we needed.

Tofu was also a staple diet of the city’s many monks and novitiates.

Our family was considered blessed to have a mother work in such a highly regarded establishment as Sayadoufu Moriku.

The mamma sans and patrons of the geisha and geisha houses in Gion would come to Sayadoufu to buy the silken tofu for their evening kaiseki.

We would also sell the little pink and purple, plum blossoms that grew on the trees lining the banks of the Katsura. These would garnish the yudofu sold in the tea houses of Ponto Cho.

At the beginning of spring my mother would carry an open wicker basket and we would pick the blossoms as we walked along the river to Sayadoufu.

Then, I would watch my mother make hiyayakku (tofu).

Watched and learned.

Observed.

Absorbed.

Floated.

And in thirty days I knew how to make tofu.

The sweep of her hands.

The sigh of her yukata.

The sway of her hair.

The scratch of her wooden clogs.

Movement.

Of mother.

Of bean.

Earth.

Together.

Step by step.

She showed me how to make tofu.

Not by word but action.

When I grew to manhood and I was conscripted to my Emperor, it stayed with me on the troupe carrier to Malaya.

On the march to Singapore.

During the malaria fevers.

As we picked out maggots from our hakumai (white rice).

The hollow, bloody victories.

The final retreat.

Burying our dead.

Shivering and shaking.

Hiding.

Surviving.

During my Buddhist novitiate.

In the jungles and the temples.

My meditation was of tofu.

And finally, when I chose to end my ordination as a monk, I decided to make tofu for my community in my new home of Chiang Mai.

In many ways Chiang Mai is much like Kyoto.

The hills.

The trees.

The river.

The many temples.

The monks.

Content people.

Forty years ago it became my home and I took residence in a room above a lane running adjacent to the old market.

My decision took many, many days to come to fruition.

But it was a decision of the spirit and the heart so my legs knew to step quietly.

It took five years to convince a farmer in the Mae On district to grow the soya beans between the rows of his rice crop.

His name was Uncle Samran.

He is still alive and tends his crops like a young, virile man.

We imported the soya bean seeds from Kyoto.

Pure, ancient seeds and we planted them in the rich, river soil of Mae On.

It took a few years to get the crop right, as the beans learned to grow between the weeds and the water channels.

Soya beans grow best in loose, well drained soil.

The natural passing of the mice, snakes, frogs and small fish of the rice fields and canals provided the organic matter for the soil.

Earth to earth.

I had to transport the ‘nigara’ (coagulant) and ‘Hinoki’ (cypress tofu moulds) from Kyoto to authenticate the process and then negotiated a way to truck the crystal, mountain water from the verdant hills of Chiang Mai.

To make excellent tofu it is essential that the ingredients are pure.

Tofu is the meat of the soil.

So, we were methodical.

Uncle and I.

Step by step.

Certain.

Deliberate.

Then when all was ready and the crop sprouted whole and pure, I spent three months making tofu for Uncle’s family.

Just to make certain my memory of mother’s tofu was still vivid.

Vivid yet gentle.

Like the swoosh and swish of the shabu shabu broth.

Everything needed to be done in order and at the right time.

The overnight soaking of the soya beans.

The gentle rubbing of the soaked beans to remove the outer skin.

Then straining the beans from the skins.

Adding the water then blending the beans to create the slurry.

Filtering the slurry and squeezing through the cheese cloth.

Filter and squeeze again.

The gentle cooking process to skim the surface foam before adding the nigara.

Finally, letting the mixture set before placing the clotting mixture in the hinoki.

More cheese cloth and just the right amount of weight on top.

Always finishing with a blessing to thank mother earth.

And with a final check of my Seikosha military issue watch, I knew we were ready.

Her timing was and is impeccable.

Watch, mother and earth.

It always takes three hours.”

He had stopped and I notice I had not been breathing but my lungs were full of pure, pure air.

And that first morning he began and I watched.

The schoolboy watching the master.

The arc of his arms and the bend of his wrists.

Elbows tucked in and head inclined just so.

The dawn light catching the orange sleeve of his robes.

And always that smile.

A small, contented smile.

The way he stood in front of the table.

Like a doctor supervising the birth of a child.

It was mesmerizing.

Magnificent.

Natural.

And as I let my mind leave my body, his hands and wrists became my mantra and I fell gently into peace, and I could see a small Kyoto woman standing behind.

The same movement.

The same energy.

And that same smile.

She was not a shadow.

She was he.

And he was she.

And I wanted what they had.

Tofu became my muse, my meat, my everything.

From earth, to mother, to man, and through service, back to earth.

A cycle.

A circle.

The web of life.

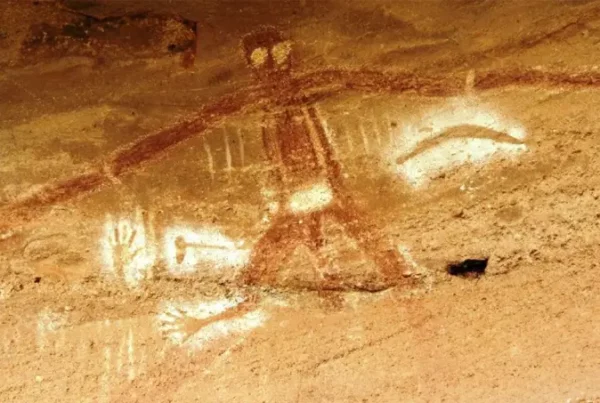

And finally, I knew this Australian man with a white father and an Aboriginal mother had come home.

This was my special spot.

Need to read more?

Purchase One Day, One Life on Book Depository: One Day One Life